One of the main reasons that so many travelers flock to Italy every year is to indulge in the rich food culture. Italian restaurants are found in every corner of the globe—yet what passes for “Italian food” in other countries is often a vague approximation of the genuine regional cuisines of Italy. Still, it would not be inaccurate to say that Italian food is the world’s most popular.

Consequently, when folks finally arrive in Italy for their long-awaited vacation, one of the first things on their itinerary is finding a quaint little trattoria and sitting down for a long, delicious, authentic meal. Too often, unfortunately, they’re disappointed.

Often lost on first-time visitors to Italy is the incredible diversity of Italy’s regional cuisines. So if you want to sample traditional recipes, then it’s best to stick to the local dishes when dining out, whether you’re at an osteria in Rome or a barcaro in Venice. And try to forget about the menu at your favorite Italian-American restaurant back home.

OK, so then what are some of the more common regional cuisines of Italy encountered when traveling around The Boot? Let’s start in the Caput Mundi…

Specialty Dishes from Various Italian Regions

Regional Dishes of Rome

One of the challenges to finding a good restaurant in Rome is that there are just too many options. This is especially true within the historical center where they are all fighting ferociously for every tourist’s Euro. Walking around Piazza Navona or Campo de’ Fiori, you’ll see an indiscrete number of establishments offering tourist menus in five or six languages. Red and white checkered table clothes abound, framed still shots from The Godfather on the walls, and Frank Sinatra bellowing from the stereo. Yet even among this circus, there are hidden gems.

OK, so let’s say that you successfully avoid all the tourist traps and zero-in on an authentic Roman restaurant. Then there’s the cuisine itself to consider, which isn’t always immediately appealing to the uninitiated straniero (foreigner). Second courses often feature various frattaglie (innards) and scarti (scraps) that, while delicious when prepared properly, don’t necessarily translate well on the menu.

Don’t despair, these “pasta alla romana” represent the most iconic pasta dishes in the whole country. You can’t go wrong with one of the four “cousins,” all a variation on the same basic recipe.

The most basic of these is the cacio e pepe, which only consists of pasta, black pepper and cheese. Tonnarelli is the pasta shape of choice, which is often called spaghetti alla chitarra outside of Rome.

If you add just one ingredient to this recipe, guanciale (fatty cheeks of the pig), you get pasta alla gricia. The pork fat makes this a tastier version than its simpler cousin, mentioned above.

From here, you have two options:

Take the pasta alla gricia and add tomato to get amatriciana.

Or instead add egg to get carbonara.

There you have it; Rome’s four most famous pasta dishes from one basic recipe.

The porchetta (a whole young pig, deboned, seasoned, and roasted to perfection) in Rome is not to be missed. The best porchetta is not actually in the city proper, however, but in the small village of Ariccia, about 30 minutes away. Here the dish has gained recognition as I.G.P., Indicazione Geografica Protetta, a guarantee by the government agency charged with such weighty issues.

Rome is also famous for artichokes, and no dish is more famous than carciofi alla giudìa. Cut into wedges and stir-fried with garlic oil and mint, the “Jewish artichokes” area typical dish of the Judeo-Roman tradition. This fried artichoke seems simple but it is not: there are several precautions to keep in mind if you want to prepare them yourself.

First of all, you need to get the right artichokes, that is to say the cimaroli or “violet,” which are large, round and without thorns. They must be cut in a special way and the frying pan must be made of earthenware, a type of ceramic, that prevents the artichoke from turning black.

Finally, the secret to perfect crunchiness: the final splash of cold water on the artichokes at the end of cooking, when they are still immersed in boiling oil.

If you want to be truly Roman in your food choice, try the fava and pecorino, typically eaten the month of May to celebrate the Italian version of “Labor Day.”

Regional Dishes of Tuscany

Perhaps Tuscany, even more so than the rest of Italy, brings to mind the hearty bounty of rustic food paired with heavenly wines. What’s more, even the word “Tuscan” has found a freakish sort of marketing power outside of Italy for everything from furniture design to gated golf communities to lamentable restaurant chains. Consequently, it might be that Tuscany has been the regional cuisine most misrepresented abroad.

What exactly is Chicken Florentine or Tuscan Salad, anyway?

Beyond the hype, Tuscany truly has one of the best food reputations in Italy. However, even within Tuscany there is a wide variety of local cuisines. (Of course, this holds true in all the regions, so we’ll have to do a bit of generalizing. Unfortunately.) It is outside the scope of this article to discuss all of the subtle nuances, but instead I’ll highlight some of the trends that can be found throughout the various regions, along with a few notable specialties.

There is a legend that suggests it was the Tuscan-born Caterina de’ Medici who taught the French how to cook—although comparing the two cuisines these days, it seems that the Frenchies were slow on the uptake. Tuscan cooking is simple and contains none of the elaborate sauces or complex seasonings found in the kitchens of Paris.

The food traditions in Tuscany have their roots in peasant cooking, or “la cucina povera,” as does the food in many regions of Italy. The poor folks learned to make the best out of the meager ingredients available to them. That’s why it’s laughable that so many fancy, high-priced “Tuscan” restaurants have sprung up in the U.S. and U.K., becoming the exact opposite of the real recipes cooked in traditional Tuscan kitchens.

This is apparent in the antipasti where the most common thing is to offer a variety of crostini (little pieces of toasted bread) topped with anything from chicken livers to wild mushrooms to olive tapenade to lardo (yes, that’s exactly what it sounds like: lard, or pork fat).

The bread is typically made without salt (called pane sciocco in local slang), because once upon a time salt was heavily taxed and very expensive. But bread eventually goes stale, so being ever frugal, the Tuscans use the day-old bread to make their famous soup, ribollita, with black cabbage (cavolo nero) and cannellini beans. There are also soups made with farro (spelt), which adds some extra fiber to the dish. Soups are a common first course in Tuscany and are always hearty and delicious, especially in the colder months.

Because the bread is made without salt and therefore fairly tasteless, the Tuscans compensate for this by eating it with some of their salty cured meats, which are fantastic. Some of my favorites are the prosciutto toscano (Tuscan ham), salamini di cinghiale (little salami made from boar’s meat), and finocchiona (a pork salami, well-marbled with fat and flavored with wild fennel seeds).

For pasta dishes, pici, and pappardelle are typical choices, usually served with ragù (meat sauces) made from hare, wild boar, duck (all’iretina), or other types of game. Tortellini filled with chickpeas and topped with pecorino cheese is another pasta option in Tuscany.

Grilled meats are an important part of Tuscan cooking, and wild boar (cinghiale) is probably the most well-known, although other types of “gamey” meats are served as well. They are usually cooked simply over an open flame (alla brace).

The famous “bistecca fiorentina” is a thick cut of beef that comes from the Chianina cattle and is known for being served “al sangue,” or very rare. Ask a Tuscan chef for a well-done steak and you’ll be shown your way out of his restaurant. Or at least get rough service.

Regional Dishes of Venice

Venice has gotten some bad press when it comes to their traditional dishes. This is unfortunate because, like all regions of Italy, the food traditions are an important element of the overall history and culture of this iconic city. Not surprisingly, Venice—the Queen of the Adriatic—has a particular affinity for seafood ingredients. But its cuisine is certainly not limited to fish. Fegato alla veneziana (liver) is one of the most famous dishes from this region, and fresh vegetables are also found in abundance.

So why is it so hard to find a good place to eat in Venice? Part of the issue might be caused by the surge of tourists every day, many of whom are only in town for a few hours while their cruise ship is docked nearby.

Consequently, they only have a short time for lunch and very little guidance in helping them find authentic Venetian food. Perhaps more than anywhere else in Italy, it helps to have some insider knowledge in Venice when it comes to finding the best food treasures and traditional Venetian cuisine.

If you are planning to come to Venice, you cannot miss the opportunity to try true Venetian cooking and drinks in the same way locals do. And the best way to do it is to go on a tour of the different local wine places called “bacari.” At these typical Venetian bars, you will be able to sample the famous “cicchetti.”

The cicchetti in Venice are delicious small bites, similar to the Spanish tapas, which can be eaten standing up or sitting down and which must be accompanied by the ever-present glass of good local wine at the right temperature.

The variety of ingredients that characterizes these dishes makes them suitable for all occasions, both for the finest palates and for those who dare to experiment with traditional and modern flavors and alternative twists. You will have them as an aperitif just before lunch or dinner, together with a drink. This drink, according to the good tradition, must be based on Venetian Spritz or Bellini, or accompanied by an “ombra,” which is a glass of local house wine.

The typical cicchetti can consist of half egg with anchovies, salame with polenta, fried crab claws, fried vegetables, octopus with polenta, and crab balls. The highlight is the famous baccalà mantecato (creamy cod fish). The Venetian appetizer for excellence, the one you absolutely cannot miss, consists of the “sarde in saor” (sweet and sour sardines), one of the oldest recipes, which is made with sardines marinated in vinegar and onion and then flavored with pine nuts and raisins.

Regional Dishes of Emilia Romagna

This is an area that often gets overlooked by foreigners, but believe me, the outstanding cuisine of Emilia-Romagna is quite well-respected by all Italians. Its capital city is Bologna, which is known by three nicknames: “the learned one” (la dotta) is a reference to its university, the oldest in Europe; “the red one,” (la rossa) originally referring to the color of the tile roofs in its historic center, but this term is now connected to the political situation in the city (i.e. the hub of the communist party); and “the fat one,” (la grassa) which refers to its rich cuisine. It is here where we’ll begin our discussion.

The food of Emilia-Romagna, while delicious, is anything but light. Butter is often used instead of olive oil and you can go days without seeing a vegetable on your plate. The cuisine depends heavily on meats and cheeses. In my opinion, these are best enjoyed either as an aperitivo or as an antipasto for your meal.

All the usual suspects are well-represented here: Prosciutto di Parma and its nasty little step-brother culatello, as well as coppa and salame da sugo. You’ll also likely find mortadella on your antipasto plate; which is what we lamentably call, “bologna,” or worse “boloney” in the U.S. (Mom never put this stuff in my lunchbox!). And of course, there’s the undisputed king of all cheeses, Parmigiano-Reggiano, which seems to find its way onto every dish in one form or another.

I know all of this sounds incredible, and it is, but please leave room for a primo piatto, because some of the best pasta recipes come from this region. I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the famous bolognese sauce right away. In the rest of Italy, it’s called ragù alla Bolognese, but in the city of Bologna itself, it’s just ragù.

The pasta itself is a wonder; rich sfoglia made with eggs and durum flour, usually in the form of tagliatelle or pappardelle. Then there are the many varieties of filled pastas, such as tortellini in brodo, tortelli di zucca (pumpkin), and various incarnations of ravioli.

Last but not least, there’s lasagne alla bolognese, which is often made with green (spinach) pasta and layered with ragù, béchamel sauce, and generous amounts of Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese.

You might not want dessert at this point, but if you must, zuppa inglese is the one to try in this region. Or, if you’re feeling a little adventurous, you might just have a scoop of vanilla gelato or some fresh strawberries (if they’re in season) drizzled with balsamic vinegar syrup from nearby Modena. It’s considered the best vinegar in Italy, as coveted as fine wines. And yes, it’s often sweet enough for dessert.

Regional Dishes of Sicily

Sicily has endured a rough history. First settled by the ancient Greeks, it was subsequently sacked by the Romans, the Goths, the Moors, the Normans, the Spanish and then finally two World Wars. Through all of these turbulent times, Sicilian cuisine adopted the best food traditions from every other culture that invaded its shores and conquered its people. Then once the occupiers left or were driven out, the food stayed behind.

In Sicily, where the sun is hot and dry, the cooking is—not surprisingly—fresh and light. This is an abundance of vegetables and fish. Many of the heavier dishes found in the colder regions in the north of Italy (see Tuscany and Emilia-Romagna) are not found on Sicilian tables.

Seafood often appears at every course in the meal, from the antipasti to the main plate. You can start your meal with an insalata di mare, which is made from assorted marinated seafood, such as octopus, squid, shrimp, along with celery, and sometimes potatoes, dressed with olive oil, lemon and salt.

For a first course, you might want to try Sicily’s signature dish of pasta con le sarde, a tempting creation with sardines, raisins, anchovies and wild fennel.

An absolute favorite second course is the braciole di pesce spada, which are rolls made from swordfish, pine nuts, and breadcrumbs that are lightly grilled or baked with a tomato and olive sauce. This would be a good choice for a last meal request if you ever find yourself on Death Row.

If you are not a seafood lover, you can always opt for Pasta alla Norma, which is never a bad choice. It’s a maccheroni dish topped with fried eggplant, tomato, and ricotta infornata (sometimes called ricotta salata outside of Sicily).

Common vegetable side dishes in Sicily include peperonata, a spicy combination of red peppers, tomatoes, and onions; and caponata, a mixture of eggplant, olives, celery, pine nuts, onions, tomatoes, capers, and sometimes raisins.

When we think of Italy we think of pasta, right? Well, if you’re in Sicily, don’t be surprised to find couscous on your plate instead. When the Arabs occupied Sicily between 827 and 1073 A.D., they brought some of their favorite recipes from their homelands of Tunisia, Libya, and Morocco. Couscous was one of these. However, the Sicilian take on this dish is usually made with fish instead of meat, and is not as spicy as the North African version.

Couscous is a coarse grain product made from semolina or durum wheat—which is also used to make pasta. But pasta is made from the flour (farina), which is produced by grinding the wheat into a fine powder. Couscous, instead, comes from the granular pieces remaining after most of the grain has been milled, so it has a grittier texture. It’s a great base for many dishes and a lighter option than pasta, which makes it an ideal choice on those hot Sicilian days.

The Mexican Chocolate of Sicily?

This may surprise some people because we don’t normally associate chocolate specifically with Sicily. However, in the charming Baroque town of Modica, there is a tradition of chocolate production that has its roots with the Aztec Indians of Mexico. Huh?

Yes, this time it’s the Spanish we can thank for their contribution. When the conquistadors returned from the New World, they brought back with them many strange ingredients from those exotic lands including xocolatl, obtained from grinding cacao seeds.

Then as the Spanish began their dominion over Sicily during the 15th and 16th centuries, they imported the raw ingredients to the island, as well as the methods of producing the final product. Even today, this recipe remains the same in both Modica and Mexico.

Traditionally, the raw cocoa powder was combined with such ingredients as vanilla, cinnamon, or hot pepper. These days there are many different flavors made by incorporating local ingredients, such as orange zest and pistachios.

Regional Dishes of Campania

Campania is the area just south of Rome’s Lazio region. This is the part of Italy that most of us think of when we entertain our fantasies of sunny weather, Sophia Loren, and the soundtrack of those classic Italian folk songs. “O’ sole mio…”

For Italian-Americans in particular, this area holds a sentimental place in our hearts because many of our ancestors came from this region. Consequently, when we think about authentic regional cuisines of Italy, many Italian-American dishes were largely influenced by the cuisine of the Campania region.

Notice I said influenced. As we’ll see, most recipes underwent a complete makeover in the new world, bowing to the different ingredients that were locally available. Even if the names are the same or similar, the final result shows a great deal of variation from one continent to the other and can hardly be called the same thing.

A typical meal in Campania might start with a caprese salad as an antipasto. This colorful creation resembles the Italian flag and gets its name from the storybook island floating languidly in the Bay of Naples. It is the height of simplicity: San Marzano tomatoes, fresh leaves of basil, and a bit of olive oil lightly sprinkled over slices of mozzarella di bufala (buffalo milk cheese). A pinch of salt and you’re off to a great start for your meal.

You can also use the fior di latte mozzarella made with cow’s milk, but I think that the mozzarella di bufala from the Battipaglia area just south of Salerno is the best for salad purposes. It has a much higher fat content than the cow’s cheese, and therefore a much richer, tastier flavor.

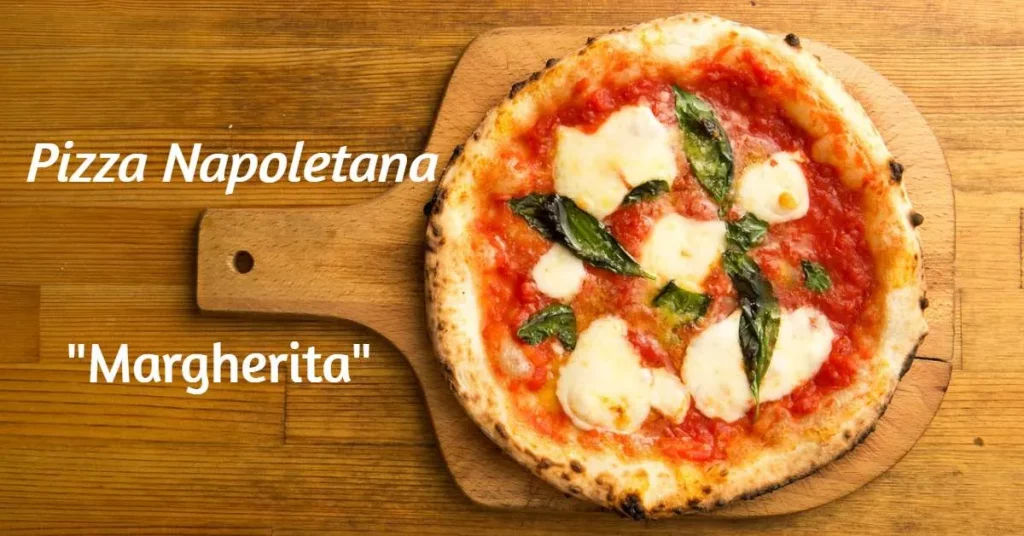

I mentioned tomatoes, and the ones from San Marzano are known throughout Italy as the most delicious, both for eating raw as in the caprese salad, and in sauces. And where you have tomato sauce, let there be pizza! Naples is the birthplace of pizza and to try the original version will make you believe that you’ve never eaten pizza before in your life.

In fact, it is so good and so original that the Italian government has petitioned the European Commission to designate Naples’ three (and there are only three) versions of pizza as Specialitá Tradizionale Garantita “Pizza Napoletana”

From the Italian Government: “In the designation “Pizza Napoletana,” we define the following names: “Pizza Napoletana Marinara,” “Pizza Napoletana Margherita Extra,” and “Pizza Napoletana Margherita.”

The products that provide the base for “Pizza Napoletana” include wheat flour type “00” with the addition of flour type “0” yeast, natural water, peeled tomatoes and/or fresh cherry tomatoes, marine salt, and extra virgin olive oil.

Other added ingredients can include, garlic and oregano for “Pizza Napoletana Marinara,” buffalo milk mozzarella, fresh basil and fresh tomatoes for “Pizza Napoletana Margherita Extra,” and mozzarella STG or Fior di Latte Appennino and fresh basil for “Pizza Napoletana Margherita.”

Are we starting to get a sense of how serious this is? These guys aren’t joking around by putting chicken, pineapple, barbeque sauce, or God knows what else on top of their capolavori (masterpieces). They take pride in doing one simple thing. But doing it perfectly.

The first course often includes seafood spaghetti or scialatielli in some form; for example, alle vongole veraci (clams). As I’ve mentioned already, seafood normally goes with the long, thin pasta shapes.

But here in Campania is where you find the exceptions made with the thick l’oro di Napoli from the best “golden” durum flour. Some typical shapes include crusicchi or paccheri—order the paccheri ai frutti di mare wherever it’s available and without hesitation. The velvety gnocchi alla sorrentina is another good choice.

Fish is abundant in this area of Italy and acquapazza (literally, “crazy water”) is a great way to cook almost anything that swims. Despite the name, the technique could hardly be more sane: you simply simmer the pesce in water with garlic, tomatoes and parsley. A little glass of white wine on the side and you have an incredible second course.

For a heartier main dish, you might try the famous parmigiana di melanzane, which of course is made by layering eggplant, mozzarella, tomato and Parmigiano cheese, and then baking it in the oven.

Now, here’s where we will highlight a few common “sins” committed in Italian restaurants abroad. Parmigiana is ONLY made with eggplant, and not with chicken, veal, or God forbid, shrimp. Americans in particular insist on their daily overdose of protein, so it’s easy to see how we’ve wandered from the path of righteousness. It’s OK, you’re forgiven. Just don’t continue to make the same mistake in the future or you’ll be swimming with the fishes yourself.

Well, we might as well exorcize all these demons. Let’s talk about polpette (meatballs). Yes, meatballs are fairly common in this part of Italy, but remember: they are a separate course to the meal and should not be indiscriminately strewn across a mountain of pasta.

And while we’re at it, let’s make sure that we have our dimensions in the correct proportion. The individual polpette should not be the size of a car battery. Rather, if you cut it with your fork, you should have two normal-sized bites.

There is also something called polpettone, which as the name implies, is bigger than a polpetta. But this is closer to what we might call meatloaf and one of them is enough to feed an entire Italian family. Or one average Italian-American goombah.

If you have a sweet tooth, then you’re in the right place. Most famously, there are the ricotta-filled pastries known as sfogliatelle, and the sticky-sweet babà, which are soaked in rum! But for name appeal, it’s hard to resist the tempting tette della regina (the Queen’s tits), which is a pastry filled with lemon cream, covered with white icing and topped with a candied cherry (you don’t really have to strain your imagination to make the association here).

To finish the meal in Campania, you must have a caffè, which many say is the best in Italy, if not the whole world. Then to “kill the coffee,” you can opt for a limoncello or one of its many variants like finocchietto (fennel) or arancello (orange). But be careful! Just because they’re sweet, don’t let them fool you—they’re strong, too. A couple of these and you’ll be singing “O’ Sole Mio” a cappella, even if you don’t speak the Neapolitan dialect.

The Authentic Regional Dishes of Italy

As we’ve seen through this whirlwind tour, Italian cuisine is NOT lacking in variety. So be careful when you talk about “Italian food,” especially when you are IN Italy. And unfortunately, unless you have an Italian nonna in your family, you’ll have to travel to Italy to try these amazing regional cuisines.